NK Cells for Dummies: Understanding the Next Cancer Paradigm

October 2nd, 2020

The growing field of NK cell-mediated immunotherapy first started almost two decades ago when it was found to be a safe and effective treatment method for those with advanced-stage leukemia.

Immunotherapy treats disease by stimulating the body’s immune response. The immune system is made of two segments:

- innate immunity: non-specific to one antigen, first line of defense that uses natural killer (NK) cells, among others

- adaptive immunity: specific to a single antigen, acquired immunity that uses T cells and B cells to invade foreign pathogens

Until very recently, the majority of pharma research was directed towards the adaptive immune system and activating T cells. FDA approved blockbuster therapies (Opdivo, Keytruda, to name a few) followed this line of thinking. In the last few years, NK cell therapies have received a lot of interest. This article will be discussing the fundamentals of NK cells and a follow-on note will focus on NK therapies in development.

NK Cells Share The Same Cancer Killing Features As T Cells

Think of NK cells as a security system for your body that roam around, looking for abnormal cells (ie. tumor or virally infected cells). NK cells are functionally most similar to a type of T cell called CD8+ T cells.

Both NK cells and CD8+ T cells are considered cytotoxic because they are capable of killing infected and cancerous cells. The difference between the two of them is the way in which they carry out this function.

How do NK Cells differentiate normal cells from abnormal cells?

On their surface, NK cells express inhibitory receptors (that turn off the NK cell) and activating receptors (that turn on the NK cell).

Normal cells in the body display MHC I molecule (inhibitory) as well as activating ligand (stimulatory). A net balance between inhibition and activation occurs when recognizing a healthy cell. Thus, the NK cell will be kept OFF (no release of cytotoxins = NO killing of normal cell).

Abnormal cells (ie. tumor/virus cells) only display the activating ligands. They will bind to the activating receptors on NK cells and signal it to turn ON, release cytotoxins and KILL the target cell.

How NK Cells Don’t Go into Killing Overdrive

Inhibitory pathways (immune checkpoints) are essential to balance the killing abilities of immune cells. These immune checkpoints maintain self-tolerance and balance the stimulatory pathways to avoid unnecessary damage of normal cells. Issues arise when this negative regulation is affected because immune cells, including NK cells & T cells, lose this “stop” ability. This can lead to an autoimmune disease.

How NK Cells Cooperate with The Adaptive Immune System

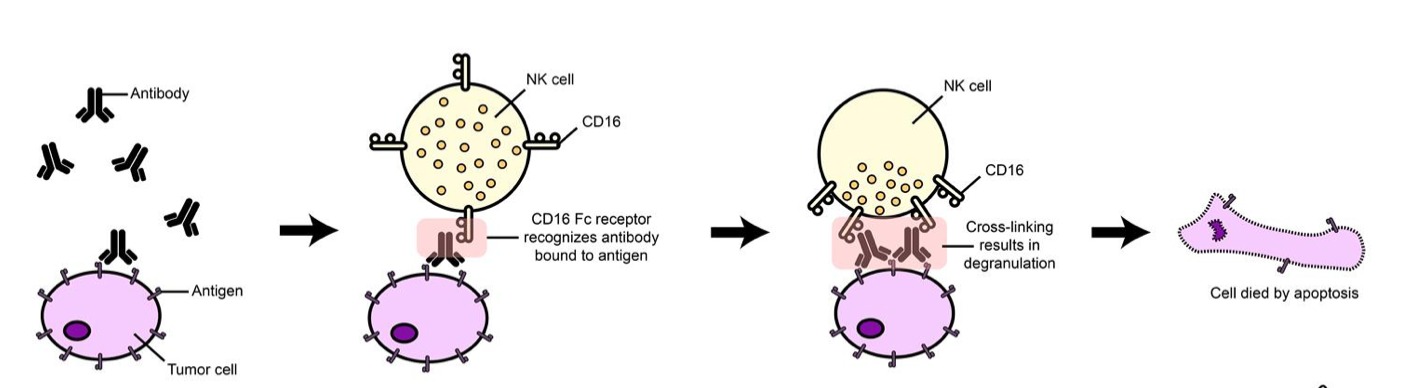

Remember the adaptive immune system includes cancer-killing CD8+ T cells and antibody-producing B cells, among others. Tumor cells express antigens on their surface (see image below). Circulating antibodies of the adaptive immune system (called “IgG”) bind to these antigens and recruit immune cells to the foreign cells.

NK cells are one of the immune cells recruited and this process is called antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC). The NK cell expresses a receptor called Fc-gamma receptor (FcγR or CD16), which binds to the antibody found on the antigen and leads to its destruction.

NK cells are not defined to one immunity over the other but rather contain functional attributes that pertain to both innate and adaptive immunity. Keep in mind that the methods of NK cell activation mentioned above are an extremely simplified explanation of how NK cells function.

Cancer Cells Can Hide, But for How Much Longer?

Cancer cells are smart and escape detection from the immune system by taking advantage of the immune checkpoints, mentioned above. By increasing their inhibitory ligands that correspond to the inhibitory receptors on immune cells, cancer cells ensure their escape from immune detection.

With T cells, blocking the inhibiting checkpoints with monoclonal antibodies resulted in the blockbuster drugs by Merck (Keytruda) and BMY (Opdivo). PD-L1 is an inhibitory ligand on the surface of cancer cells that binds to PD-1 inhibitory receptors on T cells and inhibits their cytotoxicity. Checkpoint inhibitor drugs use a monoclonal antibody (anti-PD-1) to help T cells restore their ability to detect cancer cells.

A similar approach is being taken with NK cells: targeting inhibitory checkpoints with antibodies in clinical development allows the NK cells to be relieved of inhibition and thus recognize and target cancer cells.